BEYOND THE RIVER NIGER: THE ANIOMA IDENTITY AND THE IGBO HERITAGE OF UKWANI AND NDOSHIMILI PEOPLE

By Fred Obi, 7th November 2025.

The debate over whether the Ukwani and Ndoshimili people are Igbo has persisted for sometime now, often manipulated by political interests and historical distortions. Yet, the linguistic, cultural, and historical evidence points unmistakably toward an Igbo ancestry that transcends artificial divisions.

The quest for Anioma State is, therefore, not merely about administrative recognition but a broader affirmation of identity a reclaiming of heritage long diluted by political geography. In seeking Anioma State, the people of Ukwani, Ndoshimili, Aniocha, Ika, and other Anioma areas are reaffirming who they truly are: a proud, industrious, and linguistically united Igbo-speaking people west of the Niger, deserving of a distinct political and developmental entity within the Nigerian federation.

The clamour for the creation of Anioma State is neither a new agitation nor an afterthought. It is a long-standing aspiration rooted in history, cultural identity, economic potential, and political equity. Anioma represents the Igbo-speaking people of the present-day Delta North Senatorial District a people of shared linguistic, cultural, and historical heritage, whose identity has been repeatedly misunderstood or politically downplayed.

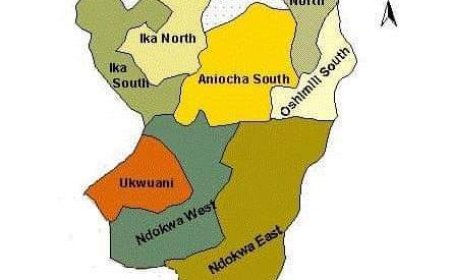

The movement for Anioma State dates back to the early post-independence era. After the creation of the Mid-Western Region in 1963, and subsequently Bendel State, the Anioma people comprising the Aniocha, Oshimili, Ika, Ukwuani and Ndoshimili ethnic blocs continued to advocate for a distinct administrative identity.

When Delta State was created in 1991 from the defunct Bendel, Anioma became the only Igbo-speaking region west of the Niger River, yet it remained politically and developmentally marginalized.

Leaders such as Late Chief Dennis Osadebay, Nigeria’s first Senate President and an illustrious Anioma son, envisioned an entity where the people could freely express their cultural heritage without being politically overshadowed. Over the years, organizations like the Anioma State Movement, Organisation for the Advancement of Anioma Culture (OFAAC), and Anioma Congress have sustained the vision. This generation, therefore, carries not just the burden but the sacred torch of continuity to realize what their forebears only dreamed of.

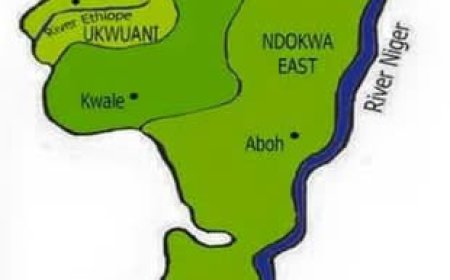

The name “Ukwani” historically referred to the Igbo-speaking people of the Upper Land a geographical and linguistic distinction made to separate them from the people of the coastal areas, particularly the Aboh Kingdom, which lies along the River Niger. Aboh was historically one of the most powerful coastal city-states, serving as a trade hub between inland Igbo communities and the coastal Ijaw and Itsekiri traders.

Originally, all these communities, Aboh, Kwale, Obiaruku, Abbi, and others were under the old Aboh Division during the colonial administrative era. With time, this was renamed Ndokwa Local Government Area after independence. Later, in the 1991 reorganization of local governments, Ndokwa was split into Ndokwa East, Ndokwa West, and Ukwuani Local Government Areas, preserving the historical distinction between the riverine and upland Peoples.

Thus, the name “Ukwani” stands as a cultural marker for the upland Igbo-speaking people in the present day Ndokwa West and Ukwani, distinguishing them from their coastal kin, the Ndoshimili (people of the riverine areas), but uniting both linguistically and culturally within the larger Igbo heritage.

The recurring debate about whether the Anioma people are Igbo or not is both unnecessary and historically misplaced. Language, culture, and historical interaction clearly place Anioma within the broader Igbo civilization. As has often been said, “If you can say ‘bia’ (come) and ‘ego’ (money) in your dialect, you are Igbo.”

These linguistic roots run deep across Anioma dialects from Ika to Enuani to Ukwani and Ndoshimili revealing a shared linguistic ancestry.

It is important to clarify that the argument of this article is not about origin, as the issue of origin is already clear and settled.

Aboh Kingdom, for instance, has well-documented historical records that trace its ancestral origin to Benin. That historical fact remains undisputed. However, what is equally undeniable is that no Aboh man today speaks the Benin language or shares linguistic affinity with it. The closest language to the Aboh man is Igbo, and that linguistic reality cannot be ignored. This does not in any way negate the historical connection to Benin, but it highlights how language, culture, and proximity have over centuries shaped Aboh’s integration into the wider Igbo linguistic sphere.

It is therefore crucial to separate the issue of origin from the issue of cultural and linguistic identity. While geographical and historical origins may point to different roots, the living language, customs, and worldview of the Anioma people, particularly the Ukwani and Ndoshimili, are inherently Igbo in character and expression.

The Ukwani and Ndoshimili peoples, for instance, share linguistic tones, idiomatic structures, and cultural values similar to the Igbos of Mba Ise, Nsukka, and parts of Enugu and Anambra. Festivals, market days, kinship titles, and even traditional names mirror the Igbo pattern.

Therefore, the question of whether Anioma particularly the Ukwani and Ndoshimili people are Igbo is no longer a matter of debate but of historical acknowledgment.

The Anioma region is richly endowed with natural and human resources. From the fertile farmlands of Ukwani and Ika to the oil-bearing territories of Ndoshimili and Aniocha, Anioma has the potential to sustain a robust economy. Agriculture, crude oil, natural gas, palm produce, and emerging industrial sectors make Anioma economically viable.

With the creation of Anioma State:

Economic management would be localized, ensuring that revenues from resources like oil in Ndoshimili are reinvested in the region.

Agricultural development in the vast arable lands of Ukwani, Ika and Aniocha could make Anioma a food production hub.

Infrastructure expansion, roads, healthcare, and educational institutions would receive greater attention under a state administration focused on the welfare of its people.

Job creation through industries and service sectors would drastically reduce unemployment, which currently drives youth migration to other regions.

Politically, the creation of Anioma State will address the long-standing imbalance in the South East geopolitical zone, giving the Igbo nation six states like other regions. However, even if it remains within the South-South, the political autonomy will enhance representation and participation, ensuring that the Anioma people have a louder voice in national affairs.

It would decentralize power, bringing governance closer to the grassroots.

It would preserve cultural identity, allowing Anioma people to promote their dialects, traditions, and institutions without external domination.

It would also enhance national unity, as state creation remains a tool of political inclusion in Nigeria’s federal structure.

Whether Anioma should belong to the South East or remain in the South South is, at best, an administrative argument. The essence of state creation is self-determination and development, not the label of geopolitical grouping. If Anioma is located in the South East, it naturally completes the Igbo-speaking circle of states. If it remains in the South South, it provides the region a balanced ethnic diversity and strengthens its political weight.

The key point is that Anioma’s destiny must not be constrained by geography but guided by justice, cultural identity, and developmental aspirations.

Indeed, the Ukwani and Ndoshimili question whether we belong to one region or another must now give way to the more fundamental question of development, dignity, and self-governance. Geography divides, but language, history, and shared destiny unite.

The vision of Anioma State is a generational assignment. The forefathers laid the foundation; this generation must build upon it. We must rise beyond the walls of political indifference and regional skepticism to actualize a dream that embodies self-determination, equity, and development.

As the old Aboh traders once navigated the Niger River with courage and precision, so must the present generation navigate the political currents of Nigeria with unity and determination. Anioma is not a mere name; it is a destiny waiting for expression.

The creation of Anioma State is not just an ethnic demand it is a constitutional and moral imperative for equity and balanced federalism. It represents the fulfillment of historical justice for a people who have contributed immensely to the Nigerian project yet remain administratively marginalized.

Anioma stands on the tripod of history, language, and destiny. Whether located in the South East or South South, the people’s identity, culture, and aspirations remain constant. As long as the words “bia” and “ego” find meaning in our tongues, the Anioma identity remains indelibly bound to the Igbo heritage yet uniquely Anioma in its pride and progress.

The struggle continues, and this generation must carry the torch forward, not as agitators, but as custodians of a historic vision whose time has come.

Fred Obi

Historian, Political Analyst and Public Affairs Commentator

What's Your Reaction?